|

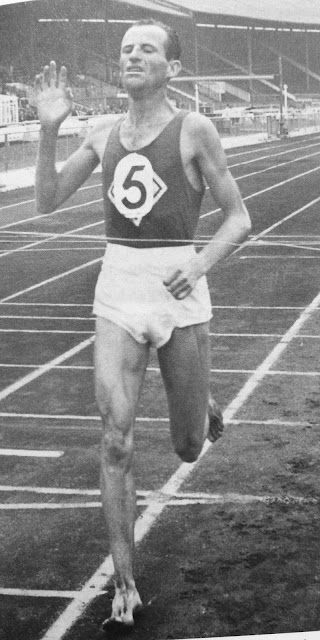

| No. 9 - Jim Hogan. |

I was skinning in Lewisham today. And, as I crept along some of the fiercest of surfaces for barefooters (tarmac with protruding gravel), I wondered how my uncle ever coped with this. My uncle is Jim Cregan, though he ran under the name of Hogan.

My uncle was born in rural Limerick in 1933 and when he was a boy he discovered both a passion and a talent for running. So naturally, his mama took him off to the local Niketown, bought some massive spongy trainers for him to run in, he slipped them on, and the rest is sporting history. No, there wasn’t a whole host cash sloshing about in Southern Ireland before the war. He had no shoes, so he learned to run barefoot.

I’ve recently been reading some of the debates about barefoot running that I try to avoid, and the reason that I try to avoid them is that I don’t really think that there is much to debate with people who think that ‘better’ running is ‘faster’ running, because I think that better running is the running that makes you feel good; the running that doesn’t hurt or injure you, and if that means running barefoot, then that’s what you should do.

I’ve recently been reading some of the debates about barefoot running that I try to avoid, and the reason that I try to avoid them is that I don’t really think that there is much to debate with people who think that ‘better’ running is ‘faster’ running, because I think that better running is the running that makes you feel good; the running that doesn’t hurt or injure you, and if that means running barefoot, then that’s what you should do.

In one of these debates, about a ridiculous experiment to decide whether forefoot or rearfoot running was best (why does this matter?) one of the trollers said something along the lines of ‘If you can just show me the marathon runner that won barefoot, maybe I’d be prepared to listen.’ And I remembered Uncle Jim.

Jim Hogan was not a barefoot exponent. He mostly ran barefoot, but his trainers did manage to wrestle him into trainers. But, he just did not like the fact that he couldn’t feel the track anymore when he ran in them.

My uncle, managed to win marathons barefoot. He competed in two Olympics. He held the world record for the 40K. In 1966, he won the European Championships, running it barefoot, in just 2.20.

He is not so well now, but is celebrating his eightieth birthday. He gave up running only a couple of years ago.

What a hero!

God bless you, Jim - and Happy Birthday.

God bless you, Jim - and Happy Birthday.