So

you wake up, and you have no idea what the day has waiting for you. The pace is

recognisable; the landscape is a familiar Sunday. Then you go for a

run and instead of the pain and exhaustion that you have been trying to run

through for weeks, your veins suddenly run champagne.

It

has been a bad month or two. My

asthma got so bad that I leant on some steroids for about a week. They made my head

feel wrong. I

lost sleep because I would ping awake at three or four in the morning, so would

get up and get ahead with my work and emails. By four in the afternoon I would be

exhausted, but my asthma was perfect. After

a few days I felt ready to run again, but I only managed a couple before I was

taken down with a cough that everyone seemed to get. Another ten days

or so. I

finally felt ready to run, did a couple. Then,

after spending a morning hunched in bed, writing, my back gave out, so I couldn’t run for another two weeks or so.

I

gave myself the all-clear about a week ago, so set out. I couldn’t believe what had happened.

This

was a major setback. How could my calves hurt so much after all the mileage I

had put into them?

I

had just got to halfway with my marathon sponsorship and it felt like all my

hard-won fitness had the longevity and sustainability of a Greek Euro.

I

didn’t

stop. I

have been two days on, one day off ever since. Doing what I can manage. They have been

hard, unfulfilling, runs. None

of them reminded me in the least of why I was doing any of this.

I

don't quite know where the day went, but it was suddenly the middle of the

afternoon and I was supposed to have headed out in the morning. I quickly change

as some of the light is already going, and I am angry with myself for having,

yet again, to run in the dark when I had wasted the day sat at my computer.

I

step out, and my legs, for the first time in a couple of weeks, don't feel

tired. I

follow my familiar route. The

sun is setting. I

will be finishing this run in the dark. Again.

The

air's heavy and dank. Not too cold. Everywhere

droplets glisten, but this water fell from a cloud and hasn't moved since it

got here, days ago. The

atmosphere is too heavy for it to evaporate into. How can a cloud

evaporate into a cloud?

It

is not until I turn onto Blackheath that I see the thick banks of fog that

gather, just like cumulus clouds, directly above the point where moisture is

trying to escape. Where

there's grass, there's fog. The

sun is setting, too, leaving bright pink candy stripes across the sky that

shimmers through the mist. I

laugh because the thing that it looks most like is candyfloss. Summer has

leap-frogged autumn and met winter.

Wordsworth

loved mist precisely because of the manner in which it prevented him from

seeing. The

'Mont Blanc' sequence in The Prelude

is when he is at his most

eloquently

disappointed

by 'the desert of the real'. For

days he climbs The Alps, his anticipation swelling with every crunching step

towards the summit. The clouds part. The

summit of Mont Blanc is lain before him in bright sunlight. And, he 'grieved to

have a soulless image on the eye.' The

hierarchy of perception dictates Wordsworth's relationship with the place. He

expects an aesthetic experience, but he gets a natural one. He prefers the

mist. It

is intellectually fructifying. The

boundlessness of his imagination is free to envision this moment of communion

in numerous ways, but Wordsworth's 'real' experience reduces it to one. Mont Blanc is

revealed. It is bald, plain. Only on the descent do the limits of his

imagination begin to shimmer once again as they fail to recall the reality of

his memory. As his descent continues, he

is able to take ownership of the place by forgetting its actuality. In an inversion of

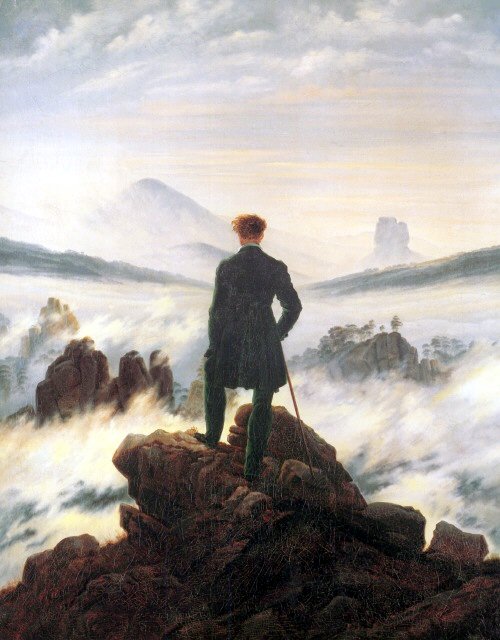

Friedrich's The Wanderer above the Sea

and Fog, Wordsworth descends below the clouds so that he can become the

self-proclaimed conqueror of his land once again.

There

is something unpleasantly coercive in Wordsworth's relationship with nature. He

seems to want to not want it. His idea of it is more important. Nature cannot

exist on its own terms, and here it seems to become a psychological

construction. A

theatre in which Man may celebrate his divine powers of creativity. A proscenuim to

frame his own ideology.

There

is something unpleasantly coercive in Wordsworth's relationship with nature. He

seems to want to not want it. His idea of it is more important. Nature cannot

exist on its own terms, and here it seems to become a psychological

construction. A

theatre in which Man may celebrate his divine powers of creativity. A proscenuim to

frame his own ideology.

I

love fog. Obviously

not because the air is even more difficult to breathe than normal. And not because it

keeps a 'soulless image' from my eyes. Or

is it? I

think I love it because it randomnly selects and deselects aspects of the

landscape that we would never think to rest our eye upon. Unlike snow, it

does not come to rest in predictable places. In seconds, it can change everything.

I

should be sensible and keep my run short. But

I can't not divert into Greenwich Park with the heath looking so magical.

Erasure

and focus. Telescope and microscope. Grayscale and technicolour.

Fog

alters the way that we can look at a place. But if you close your eyes, it

sounds different, too. The

acoustics are not so eidered as they are by a quilt of snow. It's more like a

century or two of forest has sprung up around you. Open spaces are suddenly

private and enclosed ones. Pathways

in your vision suddenly close and your eyes must find a new route. Like the

landscape has become braille, you have to feel your way through it.

When

I first enter the park it is a disappointment; this is not why I am going

overdrawn in my energy bank. Too

much of it is hidden from view. The path goes off in three directions, but they

are so stunted that they look more like the tines of a fork than long and

winding waythrus. Just

like on the Heath, the fog has landed on the ground like dollops of mashed

potato and in seconds I'm through and the landscape is renewed.

Canary

Wharf, a clutch of buildings I usually dislike because of their sturdy

dominance of the London skyline (like two tectonic plates of Meccano collided a few millennia ago), looks fantastical. The fog rests so

heavily that the ground and the river that separates us has disappeared altogether leaving the buildings to

float above this sea of clouds. The

sky is still pink from a setting sun. The

interior lights of One Canada Square usually look steely-white against a night

sky, but the grey of the fog does something altogether different to them.

Grey,

even as a metaphor, is supposed to signify absence.

Without

colour, without character, it is ‘grey’. But the grey of the fog seems to lend

itself to its surroundings. For

this dusk, the lights of One Canada Square sparkle with a deeply affluent gold.

The

building next to it is trimmed with

neon tubes of shimmering teal. These

are the same lights that have always been there, so the grey of the fog cannot

be 'no colour', but one that gives itself to others. Grey is only grey because it has given itself away. It has made this magnificent cloud city.

I

turn my back on this sight and head for home, into the mist. And as I run into another cloud on the land,

for the first time in months, I feel not like I could go on forever, but at last,

that I might want to.